When all those around you lose their heads, how do you keep yours?

Posted on / 22 Jan 2019

By Laurence Mulchrone

Live events in outdoor settings present a rare combination of challenges. Characterised by large, and often unruly, crowds of people – these events rely on completely temporary infrastructure and support. Local authorities are prone to demanding that events have little to no impact on emergency services, meaning that organisers are required to provide and manage their own response crews – whilst concurrently making public safety decisions at the same level as police incident commanders or senior fire officers.

Communication – why event management requires a deeper focus

Needless to say, combining these public health issues with the concrete, immovable deadlines of music festivals and outdoor concerts, means effective communication amongst event management teams can not only make or break a show, but also define life and death situations. Outside of military scenarios, such critical situations are only prevalent in the 999 services, the oil and mining industries, and the merchant navy – thus justifying the ongoing conversation about crisis communication and effective pre-planning for event design and management.

This blog post aims to analyse communication at live events from two perspectives, that of site and safety management, and that of production management. If you would like to contribute your ‘comms horror stories’ then do so via email – we’ll feature them in a future follow-up post.

Getting the message through – filtering, triage, and holding.

Mega-events, such as the Olympic Games, are staffed by innumerable thousands of stewarding, security, and technical staff. The sheer number of eyes and ears ‘on the ground’ can be staggering, and when combined with modern CCTV and other monitoring equipment, the amount of raw information being generated about crowd behaviour or situational context at a large outdoor event is gargantuan.

Modern organisational theory, in the context of both man-management and operations, favours flat structures and simple hierarchies – with low power distances between decision makers and boots-on-the-ground. For the reason described in the paragraph above, this model is utterly inappropriate when dealing with mega-events – the rigours of which demand extensive hierarchical structures where communication is facilitated in a formalised manner, with clear escalatory paths and responsible persons. Site management and crowd safety teams must design and use communication pathways to ensure they are not bogged down in non-critical decision making, whilst production managers and artist liaison staff must ensure proper role definitions and sufficient subordinate staff in order to ensure that the broad brush strokes of a production are in place before worrying about the gripes of bottom-of-bill band members.

Based on extensive observation and experience at a huge number of outdoor events, the Puxley team has formulated three cornerstone communication practices that Site Managers and Production Managers can employ.

Filtering

In a senior role at any event, there are certain pieces of information that you do not need to know. Less experienced event managers usually lean toward hyper-awareness, insisting on knowledge of every incident no matter how small. Although this is commendable, one must quickly learn that keeping a clear mind is vital for effective crisis decision making. If security contractors and medical teams have been employed for the event – its crucial to allow them to do their job. Most security or medical managers would be delighted to avoid managerial involvement in their decisions – take advantage of this fact. For larger events, production managers and site managers must teach their subordinates how to filter crucial information – working on a continuous improvement basis.

Triage

Even when irrelevant information has been filtered out, situations can arise when multiple reactions are required from a single decision maker. For site and safety teams, the triage process is relatively simple. Firstly, deal with protection of life – for instance by dispatching a crew to repair a broken scaffold. Secondly, deal with the show itself – perhaps by dispatching an electrician to restore power to a tertiary festival stage. Thirdly, deal with making peoples live’s easier – i.e. laying straw or wood bark in muddy areas. Production managers have a more complex task when triaging their own decision making – and naturally each show will present its own idiosyncrasies. Although many bands have demanding tech and hospitality riders, production managers may nonetheless wish to prioritise the experience of the paying customers over and above meeting last minute demands from performers. A fine line must be walked – so don’t skimp on artist liaison staff. A well defined stage manager and artist logistics team will mean production managers and contractor production crews can focus on delivering the technical aspects of a gig.

Holding

Crisis can occasionally be subjective. Various event site staff may well have their own definitions of a crisis situation – and after using the above two steps to reduce decision load, one may wish to employ a third in some situations. Conceivably, an incident will arise that requires the attention of the site/safety manager or a production manager – but is not time critical. In these cases, simply holding the information for a pre-determined amount of time may see the issue resolved before a proper reaction is needed. For instance, a large music festival requires a temporary water supply installation to service campsites and catering concessions. In some cases, information regarding a standpipe stoppage or other supply fault may reach the site office – inducing the dispatch of a plumbing team in a site vehicle. What may not be accounted for, however, is the possibility that extraordinary load on the water supply elsewhere on the site may have triggered the stoppage. Simply employing a “wait and see” approach for around 30 minutes would have shown that, in fact, there was no problem to respond to. Both site managers and production managers can use the holding approach – but it takes years of experience to learn where it is appropriate. Naturally, when in doubt, act quickly.

In Conclusion

Part 1 of this blog series aims to show just how important it is to consider communication skills. Correct information influences every decision we make – and equipping ourselves with the right conceptual tools to deal with this is time well spent. However, real world tools are just as useful in a practical sense – and so the next instalment draws upon a host of pragmatic examples and anecdotes, with stories and advice from not only the Puxley team but also a very special interview guest. Stay tuned!

Latest Articles

Gigs and Global Warming

Scientists from the international community agree undeniably that "Human influence is the dominant cause of global warming". The next century is likely to p...

Posted / 1 Dec 2019

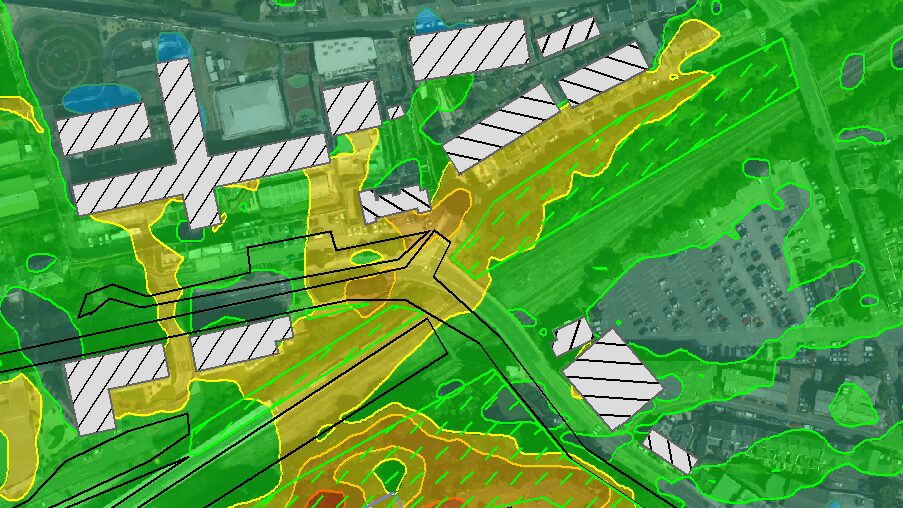

Concert Noise Management

As record sales continue to dwindle across all sections of the music industry, concert promoters and record labels have now fully embra...

Posted / 11 Nov 2019

Festivals — Managing off-site noise

The news that a new festival is coming to your neck of the woods can be greeted with great enthusiasm (if you're a festivalgoer), or great trepidation (if you a...

Posted / 19 Apr 2019