Optimise information management with advice from a real-life Action Hero

Posted on / 9 Feb 2019

By Laurence Mulchrone

Our last blog post (Part One) offered a somewhat conceptual take on communication at live events, albeit with some real world examples added into the mix. For Part Two, we are lucky enough to have secured an interview with a real-life action hero — someone to whom effective information dissemination is a life-and-death defining factor on an every day basis.

Drawing Parallels – what can we learn from other professions?

We spoke to Andy Bachelor, a professional Search and Rescue winch operator, about how he copes with the challenges of effective communication in crisis situations.

Can you briefly describe your role with the Search and Rescue service?

I fly as part of a SAR (Search and Rescue) helicopter crew that consists of 4 members – captain, co-pilot, winch/mission systems operator (my role), and winch-man/paramedic. Our helicopter is fitted with 2 electrically powered winches, mounted side by side, each with 300’ of cable and a safe working load of 600lbs. When acting as winch operator, I’m required to lower the winch-man to casualties below; this can entail guiding onto ships, cliffs, rocks, mountains, or even into the water itself. Naturally, this has to occur during both day or night and in all imaginable weathers. Aside from the winch-man, I have to factor in any equipment required, and when ready recover both crew and casualty to the aircraft. The winching procedure requires the pilot to move the helicopter in 3D dimensional space under my direction, whilst I concurrently operate the which itself.

The mission system, also my responsibility, comprises of a thermal imaging camera, daylight and low light TV, and several powerful searchlights – all of which aid us in finding casualties. The system also encompasses a comprehensive communications network, with around 7 different radios, direct cellular and satellite phone up-links, and a secure connection to the civil emergency services.

“Accuracy, Brevity and Clarity. Bearing this in mind pushes us to convey accurate information with the minimum words!”

Andy Batchelor on the ABC principle of effective communication

Are their any particular tools or methods, both mental practices or physical technologies, that you consider crucial to communicating with a flight crew?

Methodologically, we have a robust set of standard operating procedures (SOP’s) that are unified across all crews. Crucially, this cuts down the requirement to talk – as we all know what one other is supposed to do in any given scenario. One of the simplest and most important practices is strict intercom discipline – i.e. no unnecessary chit-chat. Luckily, The SOPs also indicate when certain things will happen at certain stages in the flight – reducing our need to talk and allowing us to focus on safety-critical tasks.

Furthermore, we have a pre-defined set of words and phrases, almost like our own language, which helps to cut down on a lot of extraneous chatter – stopping us using 10 words to describe something when 1 will do. This is combined with triaging and prioritising communications, i.e avoiding interrupting the winch sequence in order to answer a low priority radio call. Prioritised allocation of information flow is very important, meaning all crew must understand the gravity of all incoming communications. We work together to triage inbound information – but this of course comes with extensive practice and training.

Monitoring the plethora of communication channels may sound confusing, but with experience we learn to subconsciously filter information – internally categorising it as relevant/not relevant or applicable/not applicable. This skill takes time to develop and is an essential part of the SAR process.

Technologically, the aircraft is extremely noisy – rendering communication impossible without an intercom system. The pilots remain at the controls at all times, but the winch crew need to move around the cabin area. To enable this, we wear flying helmets with integral microphones and headsets to facilitate communication on the aircraft. These are fed by a complex intercom system, which can be wired or wireless depending on context. Critically, we have the ability to isolate the intercom system from the pilots – leaving them distraction free when flying in challenging weather and allowing the winch-man and I to discuss casualty treatment in the rear of the aircraft. Additionally, the various radio and telecoms networks are routed into the intercom, so despite being isolated, we can retain situational awareness. Ultimately, our environment means that a combination of technology, SOPs, and metal process are all vital to efficient and effective communication.

Can you summarise the extent to which communicating with your flight crew is backgrounded when you are operating the winch? Are you able to focus on the physical activity, or are you required to pass information between yourselves even at crucial technical stages?

There is some backgrounding of external communications during winching – the flying pilot, operator and winch-man may mute the volume on non-relevant radio’s – allowing us to concentrate on the precision task in hand without distraction. Nonetheless, the flight crew need to communicate internally, even at the most precise stages of a rescue operation.

When deploying or retracting the winch man, accurate and concise communication is vital. Once we are directly above the casualty, the pilot’s view of the winch area is completely obscured, with the casualty both behind and below him. The pilot thus has to rely on me, the winch operator, to pass directions to him so that he can manoeuvre the helicopter. We employ a system called ‘voice marshalling’, where a small number of precisely defined words and numbers indicate which direction the pilot needs to fly – yet another example of rigid SOPs in action. The importance of accuracy in this situation cannot be emphasised enough. It only takes a single mis-heard command with the rotors 15’ from a cliff face to turn a successful rescue into an accident! For this reason, the only people using the intercom should be the winch operator and the flying pilot. Concurrently, the winch-man below uses hand signals to indicate when he’s at the right height, or to fine tune his arrival point. Although the winch-man has the ability to use the wireless intercom, he communicates solely by using these signals in order to avoid interfering with the communication between the pilot and winch operator. This might sound old fashioned, but as an alternative method of communicating it works perfectly – keeping channels free for pilot and operator to coordinate the aircraft position.

Fundamentally, the crew must background a certain amount of information, but equally we can’t afford to miss any crucial communication that may be sent to us regarding the task at hand. There are three essential tactics we employ to achieve this:

- We allocate external radio monitoring to the crew member with the least direct involvement with the winching procedure (normally the non flying pilot)

- Unless it’s a major emergency (e.g. engine failure) no-one speaks on intercom while the winch operator is guiding the pilot, minimising any interference and ambiguity.

- The winch-man has a need to communicate with the winch operator during the process. To do this, he uses a formatted package of hand signals – a visual alternative to audio which keeps the intercom free for the operators voice commands.

“…if everyone knows what they are supposed to be doing, and when they are supposed to be doing it, unnecessary chatter or over-talking is cut down dramatically.”

Andy Batchelor on the importance of operating procedures

Is there an example of a rescue scenario where calm and effective communication between the flight crew was crucial in responding to a change in situation?

Honestly, this happens on pretty much every rescue. It’s most vital, however, when things go wrong. In the past, a rescue operation ended up with the winch wire becoming entangled around masts and ropes on the back of a ship. In this case, calm and accurate communication was vital to make sure we untangled the cable without it snapping!

Is there anything else you would like to add regarding the topic of verbal communication, communication technology or theory?

In essence, our communications system is structured around speaking a common language. We all use the same words, with a view to mutually understanding situation or context without the need for extensive explanation. On a wider level, we employ the “ABC’ approach to communication – “Accuracy, Brevity and Clarity”. Bearing this in mind pushes us to convey accurate information with the minimum words! Moreover, a significant tool to optimise communication is a robust set of SOPs; if everyone knows what they are supposed to be doing, and when they are supposed to be doing it, unnecessary chatter or over-talking is cut down dramatically. Training is important, as it develops the mental process whereby you can take in multiple communications at once – whilst at the same time filtering the wheat from the chaff. Finally, technology is crucial – we couldn’t work without it – but we still employ tried and tested hand signals to help minimise chatter during critical periods.

Practical methodologies – how do successful events manage information?

In the real world, communication will never happen perfectly. Event decision makers can be safe in the knowledge that even considering their communication efficacy puts them ahead of the curve. Continuous improvement is the name of the game – and the we’ve put together a toolkit of technological and methodological practises, drawing upon Andy’s and our own experiences, which may help along the way:

6 Principles of Crisis Communication – This theoretical framework, produced by the American government, outlines relatively simple ways to ensure the most critical of messages are processed properly.

- Be First – don’t let uninformed parties disseminate incorrect information before you.

- Be Right – not an easy one, but it’s better not to make guesses regarding causation of an incident. Either tell the whole truth, or as much of it as you are aware of.

- Be Credible – use honesty and admit what you don’t know. Remain professional, sober, and confident when delivering important information. Believe in what you say.

- Express Empathy – whether its telling a bottom-of-bill act that their set has been cut short, or notifying a catering concession of revocation of their traders permissions, try to put yourself in the shoes of those receiving bad news.

- Promote Action – where possible, offer legitimate solutions alongside crisis information.

- Show Respect – this promotes co-operation, understanding, and support from people affected by the information you are giving.

ABC Approach – This tactic is illustrated perfectly in our interview with which operator Andy Bachelor. Aiming for Accuracy, Brevity, and Clarity in communication makes things easier for everyone.

Event controllers and event incident logs – A large event should employ dedicated radio network operators, trained to aid in the Filter, Triage, Hold process. They should provide written logs of significant incidents, and be the single point of contact between teams. Choose them wisely.

Hierarchies, Command Chains, and Role Definitions – Formalising management hierarchies is a vital part of the event management planning process. When snap decisions need to be made, their must be no question about who makes them. Clearly defining the roles of all your staff is also crucial – even if that definition is that of “jack of all trades”.

A Common Language – The “Drawing Parallels” chapter of this post shows us that rigid, pre-defined terms and procedures cannot be ignored. In the world of live events, this takes multiple forms. Defining radio-network codewords is an easy first step – and is often used to avoid saying alarming words such as “fire” over a public network. Like any technical industry, complex terminology and buzzwords are rife – but often this can be leveraged to cut down on irrelevant information. Choose experienced event crew, despite their higher price, and the advantages will become self-evident.

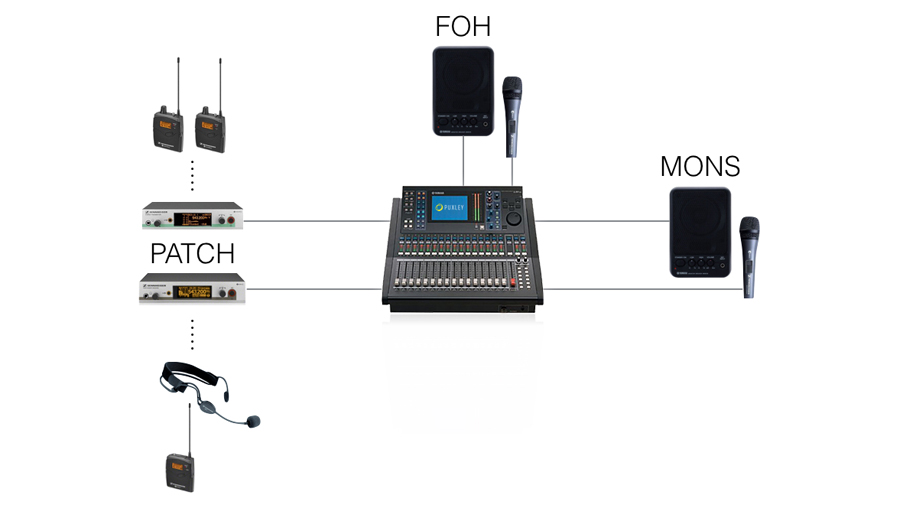

PA and stage comms packages, radio networks, and fail-safe communication. – Production managers should consider stage/FOH comms packages using infrastructure outside of the event site radio network – for the simple reasons of resilience and privacy. Site managers should never skimp on radio technology – as range and battery life can quickly become an issue with cheaper models. For high risk events, such as extreme sports or those with large crowds in urban areas, backup comms options should be made available. Music festivals have been known to crash cellular networks, so having a satellite phone or police radio on-site can provide a contingency form of emergency communication.

Dealing with non-pro crew – Volunteers, artists, part-time stewards, and all sorts of other well meaning non-pro crew can often hinder well designed management processes. Ensure these parties have a clear point of contact that can filter, triage, and hold information before it is escalated to site/production managers.

Stay tuned to the Puxley Blog and Knowledge Base for our technical-rundown of Stage/FOH comms systems. Need help designing and implementing complex event comms or networking? Contact our team of experts.

Latest Articles

Gigs and Global Warming

Scientists from the international community agree undeniably that "Human influence is the dominant cause of global warming". The next century is likely to p...

Posted / 1 Dec 2019

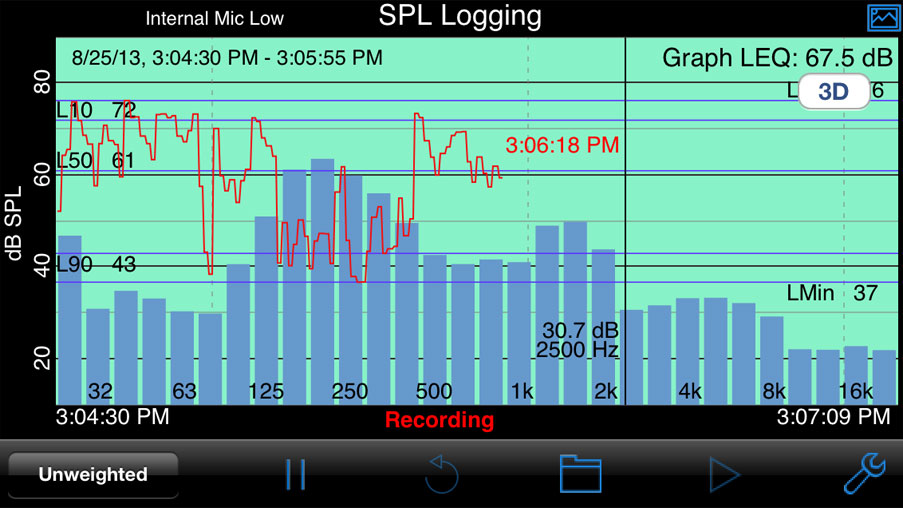

Concert Noise Management

As record sales continue to dwindle across all sections of the music industry, concert promoters and record labels have now fully embra...

Posted / 11 Nov 2019

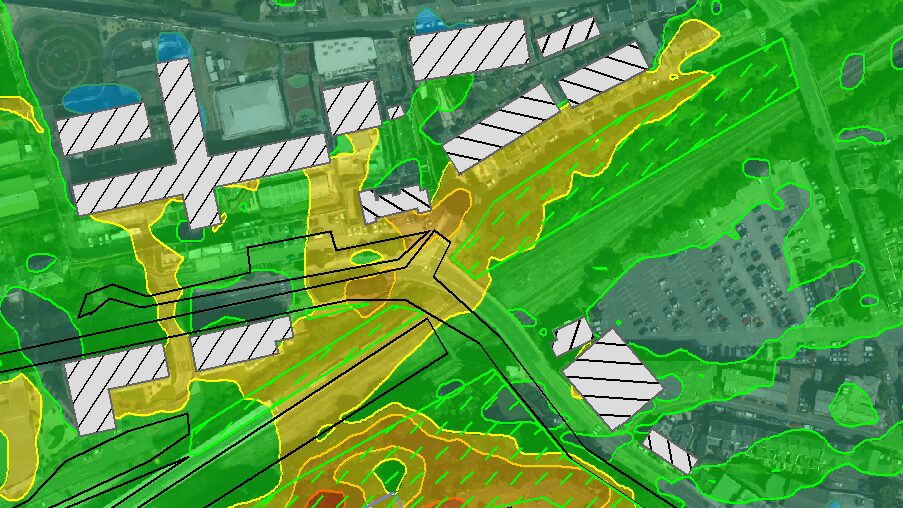

Festivals — Managing off-site noise

The news that a new festival is coming to your neck of the woods can be greeted with great enthusiasm (if you're a festivalgoer), or great trepidation (if you a...

Posted / 19 Apr 2019